|

Raoul

Wallenberg: A Hero For Our Time

By Rachel Oestreicher Bernheim, 1981

A monument to Raoul Wallenberg

by the Hungarian Sculptor |

Prologue

In Tribute

In

these dark and cynical times, when there is so very little

for mankind to believe in, when the historian and the investigative

reporter have trained us to expect the worst of the great,

it is little wonder that the world does not quite know what

to make of Raoul Wallenberg - or that too many governments

have chosen to maintain a shameful silence.

Sadly,

noble words are robbed of their meaning. We hear him called

"righteous Gentile," "hero of the Holocaust,"

"unsung martyr of World War II." Now and then

some scholar addresses himself anew to the question of how

and by what means Wallenberg managed to save one hundred

thousand lives, or probes the psychosocial impulses which

compelled him to forsake wealth and ease and undertake so

dangerous a mission.

But

when we have set down the last pious platitude, made our

tallies and pondered his motives, something in Raoul Wallenberg

still eludes us. He remains a mystery, as do all pure-souled,

whole-hearted, thoroughly moral men. We are left only with

the everlasting memory of what he did - and what Raoul Wallenberg

did was to fulfill, as none in his time would or could,

the terms of the contract which binds each of us to humanity.

The Talmud summed up that contract in these words: "Whoever

saves a single soul, it is as if he saved the whole world."

Therefore

we must do more than cling to his memory. We must proclaim

to all the nations that Raoul Wallenberg lives, tirelessly

champion his cause, tirelessly press for news of his fate

- till the day, if it please God, that Raoul Wallenberg

returns to us from the long, bitter totalitarian night.

Raoul,

aged 3, with his widowed mother, Maj Wising. |

Raoul

Wallenberg was born August 4, 1912. His parents

came from two of Sweden's most outstanding families, whose

members included diplomats, bankers, and bishops of the

Lutheran Church, as well as artists and professors.

Wallenberg's birth was surrounded by tragedy. His handsome

father (after whom he was named), an officer in the Swedish

Navy and the sone of the Swedish ambassador to Japan, died

after a brief illness at the age of 23 - eight months after

his marriage and three months before the birth of his son.

Raoul Wallenberg

senior aged 23 |

Raoul's mother, Maj Wising Wallenberg, was only 21 at the

time. Three months after Raoul's birth, his grandfather

Wising died suddenly of pneumonia. Many years later, Nina

Lagergren, Raoul's half-sister said, "All

of a sudden, in that once-happy house, there were two widows

and this baby boy." The two bereaved women focused

all of their love on the child who, says Nina Lagergren,

"gave and received so much love that he grew up to

be an unusually generous, loving, and compassionate person."

In 1918, Maj Wallenberg remarried. Her second husband, Fredrik

von Dardel, was a young civil servant in the health ministry.

He later became the administrator of Karolinska, Sweden's

largest hospital, world famous for its medical research.

Two more children were born to Maj von Dardel, Guy and Nina.

Both serve as leaders of the international Raoul Wallenberg

effort.

This is page 8: Has a different picture to add

Ambassador Gustav Wallenberg, Raoul's grandfather, insisted

that Raoul receive an education befitting a member of the

Wallenberg family. Accordingly, after high school in Sweden

and nine months of compulsory Swedish military service,

Raoul was sent to Paris for a year. Then, at his own insistence,

he attended the University of Michigan

in Ann Arbor, where he completed the five year program at

the School of Architecture in three and one half years.

He graduated in 1935, along with his classmate, future President

Gerald Ford.

When Raoul returned to Sweden, his grandfather insisted

that it was time for his to begin studying banking and commerce.

This decision was to have far-reaching implications.

Raoul's first position was with a Swedish firm in South

Africa. In 1936 his grandfather arranged a position for

him at the Holland Bank in Haifa, Palestine. There Raoul

began to meet young Jews who had already been forced to

flee from Nazi persecution in Germany. Their stories affected

him deeply.

In 1939, he went to work with a Jewish refugee from Hungary

named Koloman Lauer. Lauer was owner of

the Central European Trading Company, which dealt in foodstuffs.

In eight months Raoul was a junior partner of the firm.

Raoul often traveled to Hungary. His partner had close relatives

living in Budapest. Through them, Raoul began to know the

Hungarian Jewish community.

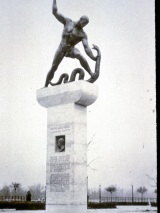

Settlements

for Jews fleeing Nazi persecution in Haifa Settlements

for Jews fleeing Nazi persecution in Haifa |

As a Swedish Christian from an outstanding family, he was

able to travel freely in Germany as well as in Nazi occupied

France. He became familiar with the eccentricities of Nazi

bureaucracy and was unusually successful in his required

business dealings with Nazi officials.

Wallenberg was increasingly concerned with the fate of Europe's

Jewish communities. Actress Viveca Lindfors,

a friend of Raoul's during his bachelor days in Stockholm,

recalls an evening when he took her back to his office.

There, he began to tell her of the plight of the Jews in

Nazi Europe. His stories, told with frightening intensity,

sounded impossible to her.

Between

March and June 1944 427,000 Hungarian Jews were

deported. In 46 working days nearly a quarter

of a million of them were exterminated.

|

In the United States, at the behest of President Roosevelt,

the War Refugee Board was established.

Its goal was to save Jews and other Nazi victims. The WRB

was well funded. Its top priority, after the partial Nazi

Hungarian occupation in June 1944, became the safety of

the 750,000 Hungarian Jews.

The War Refugee Board came to neutral Sweden, which had

an active embassy in Budapest, looking for someone who would

agree to go to Hungary. Such a person would work under the

auspices of the Swedish government with the protection of

a Swedish diplomatic passport, though representing and funded

by the War Refugee Board.

The War Refugee Board's representative in Hungary was to

be given a large sum of money and would be empowered by

the Swedish government to issue passports to as many Jews

as possible. Raoul Wallenberg was chosen to be the War Refugee

Board's representative.

On July 9, 1944, Raoul Wallenberg, age 31, arrived at the

Swedish embassy in Budapest. He traveled lightly with a

backpack and a small pistol. His primary adversary was SS

Lt. Col. Adolf Eichmann. By the time Wallenberg

arrived in Hungary, all 437,000 Jews - men, women, and children

- living outside Budapest had already been deported. The

rest of Hungary's Jewish community consisted of the 230,000

Jews living in the capital.

Wallenberg's

first job was redesigning the Swedish protective passport.

This new first secretary of the embassy found the document,

which was legal and could be issued only by the Swedish

legation, physically unimpressive. He knew that the Nazis

and their Hungarian counterparts were frequently people

of little education, who would be easily impressed by a

large, official looking document. How correct this simple

assessment proved to be!

Wallenberg redesigned the "Schutzpass."

He used the blue and yellow of the Swedish flag, and emblazoned

the document with the symbol of the triple crown of Sweden.

This passport saved the lives of tens of thousands of Jews,

as well as a great number of anti-Nazi Hungarian partisans.

According

to former staff member, Agnes Mandl Adachi,

Wallenberg printed huge placards and put them up all over

the city. The billboards, which pictured and proclaimed

the validity of the Schutzpass, were designed to make the

Nazis familiar with the document and its authority.

In the darkest days of 1944, the Swedish protective passport

even provided some humor in the midst of despair. Edith

Ernester, who lived through that time, recalls:

"It seemed so strange - this country of super-aryans,

the Swedes, taking us under their wings. Often, when an

Orthodox Jew went by, in his hat, beard and sidelocks, we'd

say, 'Look, there goes another Swede.'

A special department was created in the Swedish embassy

in Budapest with Wallenberg as its head. It was staffed

primarily with Jewish volunteers. Initially, there were

250 workers; later, he had about 400 people working around

the clock. Wallenberg seemed to sleep no more than an hour

or two a night, and then it was wherever he happened to

be working. He was everywhere.

Wallenberg persuaded the Hungarian authorities to free the

Jews on his staff from wearing the Yellow Star worn at all

times by other Jews. This simple exemption allowed his workers

much greater freedom of movement, as well as the protection

of anonymity - an essential factor in carrying out many

of Wallenberg's missions.

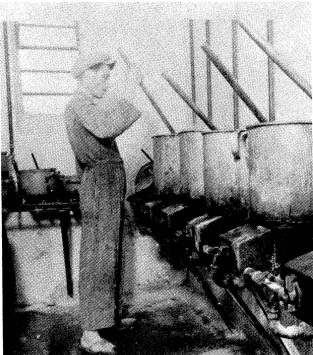

A

soup kitchen established by Wallenberg.

A

hospital established by Wallenberg. |

Agnes

Adachi recalls the night when she and her co-workers needed

to complete about 2,000 Schutzpasses and deliver them before

six a.m. when the Nazis would be rounding up several thousands

of Jewish women. She tells of working by candlelight in

a villa on the outskirts of Budapest. Wallenberg came in

and very calmly announced that the villa next door was the

Gestapo headquarters. He then smilingly assured his staff

that they must continue their work and not be alarmed. The

Schutzpasses were completed, and each was delivered on foot

before six a.m.

According to Mrs. Adachi: "He made a game out of outfoxing

the Nazis, but he played it with the utmost seriousness.

Most of all, he was like a big brother one looked up to,

and he had the most beautiful eyes that I have ever seen.

They were so beautiful and they saw everything."

Wallenberg's next step was crucial to ultimate success.

In a section of Budapest designated by the Hungarian government

as the "International Ghetto", Wallenberg purchased

thirty buildings where he flew Swedish flags next to the

Jewish Star. These buildings, and others for which he was

able to negotiate, were given the full protection of the

Swedish government.

In these protected houses, Wallenberg set up hospitals,

schools, soup kitchens, and a special shelter for 8,000

children whose parents had already been deported or killed.

Generally, the Swedish flag and the passports held by those

living in the houses were protection enough. If his spies

told him that a raid was being planned by the Nazis or their

Hungarian counterparts, young, blond Jewish men living in

the houses would be dressed in Nazi uniforms and put outside

to "guard" the houses.

Occasionally, however, all efforts failed. On Christmas

Day, 1944, a gang of Hungarian Nazis entered a protective

Swedish children's shelter and seventy-eight children were

machined gunned and beaten with rifle butts. All died.

Because of Wallenberg's swift action in setting up shelters

that offered care and protection, the other neutral legations

and the International Red Cross also followed and helped

greatly to expand the number of protected houses. After

the war it was established that about 50,000 Jews living

in the foreign houses of the International Ghetto had survived.

Of these, about 25,000 were directly under Wallenberg's

protection.

On

October 15, 1944, the legal Hungarian government of Admiral

Horthy fell and a pro-Nazi government called the

Arrow-Cross was installed. The Germans, who had previously

not been so much in evidence, came pouring across the Hungarian

border.

The Arrow-Cross gendarmes, an elite, quasi-military corps,

were Adolf Eichmann's greatest allies in his march toward

the "final solution". If possible, they were even

more sadistic than their German counterparts, and Eichmann

used their fervor accordingly.

In late 1944, with the Germans fighting on many fronts,

the end of the war and an Allied victory began to seem imminent.

This knowledge only seemed to spur Eichmann on to finish

his "purification" of Hungary.

Women

being forced at gunpoint to join a death march. |

In

this situation, Jeno Levai recalls, "It

was of the utmost importance that the Nazis and the Arrow-Crossmen

were not able to ravage unhindered - they were compelled

to see that every step they took was being watched and followed

by the young Swedish diplomat. From Wallenberg they could

keep no secrets. The Arrow-Crossmen could not trick him.

They could not operate freely. They were held responsible

for the lives of the persecuted and the condemned. Wallenberg

was the 'world's observing eye', the one who continually

called the criminals to account.

As the Germans found themselves increasingly on the military

defensive, they were less able to supply Eichmann with trains

and trucks for deporting Jews from Hungary. On November

8, 1944, as the Russian army moved closer to Budapest, Eichmann

ordered all Jewish women and children rounded up and marched

on foot 125 miles to Hegyeshalom on the Austrian-Hungarian

border for deportation to the death camps. The men were

brought to a work camp in another location.

It took one week to walk in freezing cold and snow, with

no food or heavy clothing. Women in high heels, rounded

up in the street, children, and the elderly were forced

to keep up with the pace set by the gendarmes. All along

the route lay the dead and the dying.

Wallenberg, Per Anger, then second secretary

of the Swedish legation, and their driver went along the

route of the march by car, giving out food, clothing, fresh

water and Swedish protective passports whenever possible.

On the first day of the march, they rescued about 100 people

with the protective passports. A few others they rescued

by sheer bluff.

Jews

on foot being marched westward to the border and

deportation. |

In

the days that followed, Wallenberg made repeated trips along

the march route and continued his rescue efforts at the

border. He organized Red Cross truck convoys to deliver

food and set up checkpoints for those with "Schutzpasses".

About 1,500 people were thus rescued from transport to Auschwitz.

At the end of November, Eichmann was ordered back to Berlin

by Heinrich Himmler, who was preparing to put out peace

feelers to the Allies. The marches were halted and Eichmann

was instructed to cease all liquidation efforts.

In December 1944, Wallenberg reported to Stockholm about

the death marches. "It was possible to rescue some

2,000 persons from deportation for some reason or another."

He added, almost as an afterthought, that the Swedish mission

had also secured the return of 15,000 laborers holding Swedish

and other protective passes.

John Bierman, in his book on Wallenberg,

RIGHTEOUS GENTILE, has included a moving eye-witness account

of Wallenberg's work. They are the words of Tommy

Lapid, now director-general of the Israeli Broadcasting

Authority. In 1944 Lapid was 13 years old and one of 900

people crowded into a Swedish protected house. His father

was dead, and he had been allowed to remain with his mother.

Jewish

women being marched through Budapest to a holding

cap, prior to deportation. This photograph was

taken by Wallenberg. |

"One morning, a group of Hungarian Fascists came into

the house and said that all the able-bodied women must go

with them. We knew what this meant. My mother kissed me

and I cried and she cried. We knew we were parting forever

and she left me there, an orphan to all intents and purposes.

Then two or three hours later, to my amazement, my mother

returned with the other women. It seemed like a mirage,

a miracle. My mother was there - she was alive and she was

hugging me and kissing me, and she said one word: Wallenberg."

"I knew whom she meant because Wallenberg was a legend

among the Jews. In the complete and total hell in which

we lived, there was a savior-angel somewhere, moving around."

Wallenberg became famous among the Jews of Hungary for his

many individual acts of bravery, but it was as a negotiator

that he achieved his greatest results. In addition to its

International Ghetto, Budapest had a general ghetto, which

was guarded and sealed off. The 70,000 Jews kept there as

virtual prisoners existed under the most horrible and primitive

conditions, unprotected from the violence of the Arrow-Crossmen.

Hungarian

gendarmes execute an 'uncooperative' Jewish leader. |

Wallenberg got word in the first days of January, 1945 that

a final plan, masterminded by Adolf Eichmann before he left

Hungary, was soon to be carried out. It was to be completed

very quickly, before the Russian army could enter Budapest

and open the ghetto. The plan called for the total massacre

of the ghetto population, by a combined task force of SS

men and Arrow-Crossmen led by a priest, Vilmas Lucska. An

additional 200 policemen would encircle the ghetto fence,

making certain that no Jews escaped.

All the documents for the extermination plan were ready

and the German commander in Budapest was prepared to carry

out his orders, even as the Russians shelled the city.

Wallenberg had been working behind the scenes for many months

with Pal Szalay, a high-ranking Arrow-Crossman

who was a senior police official. Szalay was horrified by

the atrocities committed by his compatriots, and he quickly

became an invaluable ally. In fact, he was the only prominent

member of the Arrow-Cross to escape execution after the

war by the People's Court; he was set free with no charges.

Szalay helped to save many lives in various incidents, but

his most important contribution was as Wallenberg's spokesman

in negotiations with the German general, August

Schmidthuber.

Schmidthuber was commander of the SS troops in Budapest,

and Eichmann had designated one of his detachments to spearhead

the ghetto action. It was far too dangerous for Wallenberg

to meet personally with the SS leader; he was already wanted

by the Gestapo, and there had been several attempts on his

life. Any direct communication with Schmidthuber would mark

Wallenberg as a dangerous international witness to the ghetto

extermination.

Wallenberg sent Pal Szalay to speak for him with the general.

Szalay informed Schmidthuber that, if the planned massacres

took place, Wallenberg would see to it that the general

was held personally responsible and would be hanged as a

war criminal. With the Russian army already approaching

the city, the general reconsidered. He issued the order

that no ghetto action was to take place. It was Wallenberg's

last victory.

When the Russian army entered Budapest, they found almost

70,000 Jewish men, women and children alive in the general

ghetto. Another 25,000 people were in the protected houses,

and an additional 25,000 persons of Jewish origin were found

hiding in Christian homes, monasteries, convents, church

basements, and other sanctuaries.

In all, 120,000 Jews of Budapest survived the "final

solution". They were the only substantial Jewish community

left in Europe. At least 100,000 of these people owed their

lives directly to Raoul Wallenberg.

In Jewish folklore there exists a tale of "36 righteous

men." This is the minimum number of anonymous, righteous

men who must be living in each generation, as the world

exists on their merit. These hidden saints appear in times

of great danger to the Jewish community, using their powers

to defeat its enemies. Perhaps such a legendary "Lamed-Vovnik,"

-or- "One of the Just" - made his appearance in

the person of Raoul Wallenberg.

The

Arrest and Disppearance of Raoul Wallenberg

On January 13, 1945 Wallenberg first contacted the Russians,

then on the outskirts of Budapest, in an effort to secure

food and supplies for the Jews under his protection.

On January 17 Wallenberg and his driver, Vilmos

Langfelder, left Budapest for a meeting with the

Russian commander, Marshal Malinovsky,

in the city of Debrecen, about 120 miles east of Budapest.

On the way to the meeting with the Soviet commander Wallenberg

and his driver were taken into "protective custody"

by the Soviet NKVD, the secret police later

known as the KGB.

The Soviet deputy foreign minister, Vladimir Dekanosov,

notified the Swedish Ambassador in Moscow that Wallenberg

was in Russian hands: "The Russian military authorities

have taken measures to protect Raoul Wallenberg and his

belongings," said the note.

When he was last seen on January 17 by members of his staff,

Wallenberg was already being "protected" by a

Russian officer and two soldiers on motorcycles. He was

carrying his knapsack, a briefcase containing his own post-war

plan, and a large sum of money. It was the last time anyone

ever saw Raoul Wallenberg as a free man.

In the first week of February 1945, after a trip by train

to Moscow, Wallenberg and his driver were placed in separate

cells in Lubianka Prison, the principal interrogation center

of the Soviet Secret Police.

That month Wallenberg's mother, Maj von Dardel,

was informed by the Russian ambassador to Sweden, that her

son was safe in Russia and would be back soon. The family

was asked not to make a major issue of Raoul's absence.

His safe return was assured.

On January 21, 1945, Wallenberg was placed in cell 123 of

Moscow's Lubianka Prison, where he joined Gustav

Richter, formerly a police attache at the German

embassy in Ruania. Richter testified in Sweden in 1955 that

Wallenberg was interrogated only once for about an hour

and one half, in the beginning of February 1945. He was

accused of spying, perhaps for the United States, since

the War Refugee Board was an American based and funded operation.

On March l, 1945, Gustav Richter was moved and his knowledge

of Wallenberg ended.

On March 8, 1945, the Soviet-controlled radio in Hungary

falsely reported that Wallenberg had been murdered in route

to Debrecen, probably by Hungarian Arrow-Cross or still

at large agents of the Gestapo.

In April 1945 Averell Harriman, then U.S.

ambassador to Moscow, was instructed to contact the Swedish

ambassador and offer any assistance necessary to help determine

Wallenberg's fate.

Swedish Ambassador Staffan Soderblom declined

U.S. help or involvement - potentially a major mistake.

A second tactical error was committed during a meeting between

Stalin and Soderblom on June 15, 1945. The ambassador told

the Soviet chief of state that he personally felt Wallenberg

was dead, killed by the Arrow-Cross, but would still appreciate

the Soviets' looking into the matter, as his government

in Stockholm had requested this inquiry. Stalin promised

to investigate personally and wrote Wallenberg's name on

a pad.

On August 8, 1947, the second important Soviet communique

about Wallenberg was sent to Sweden. Written by Foreign

Minister Andrei Vishinsky in reply to Swedish government

inquiries, the message stated that "a search of prisoner-of-war

camps and other establishments had turned up no trace of

Wallenberg. In short, 'Wallenberg is not in the Soviet Union

and is unknown to us'. The note concluded with the 'assumption'

that Wallenberg had either been killed in the battle for

Budapest or kidnapped and murdered by Nazis or Hungarian

Fascists"

For another ten years, the Vishinsky note was the only official

Russian word on Wallenberg's fate. When a group of Swedish

citizens nominated Wallenberg for the 1948 Nobel Prize for

Peace, it elicited the only public statement ever made by

the Soviet Union concerning Sweden and the Wallenberg affair:

A Soviet journal again accused the Nazis or the Arrow-Cross

of murdering Raoul Wallenberg.

For years thereafter, there was only official Soviet silence.

Then as a number of European prisoners were released in

1955, word of Wallenberg's imprisonment began to filter

back to Sweden.

On February 2, 1957, a note was delivered to the Swedish

government and signed by Deputy Foreign Minister

Andrei Gromyko. The note told of a handwritten

report by a Col. Smoltsov, head of Lubianka Prison's health

service, to Viktor Abakumov, minister of state security.

The report was supposedly written on July 17, 1947:

"I report that the prisoner Walenberg (sic) who is

well-known to you, died suddenly in his cell this night,

probably as a result of a heart attack. Pursuant to the

instructions given by you that I personally have Walenberg

under my care, I request approval to make an autopsy with

a view to establishing cause of death."

Scrawled across the bottom of the page in the same handwriting

was the addendum:

"I have personally notified the minister and it has

been ordered that the body be cremated without autopsy.

17, July. Smoltsov."

Smoltsov and Abakumov were both dead in 1957 when Gromyko

delivered the note. It is highly irregular for a Soviet

prison doctor to report directly to a minister rather than

to the head of the prison. The Russians never produced Col.

Smoltsov's note or even a photocopy of it - an important

omission, given the Russian's penchant for careful documentation.

Gromyko's communique ended by saying:

"The Soviet government presents its sincere regrets

for what has occurred and expresses its profound sympathy

to the Swedish Government as well as to Raoul's relatives."

On February 9, 1957, the Swedish ambassador to Moscow, Rolf

Sohlman, delivered a note to Gromyko from the Swedish government,

expressing outrage at the facts as reported in the Russian

communique. The note continued that the Swedish government

felt the investigation was incomplete. It also found it

difficult to believe that everything referring to Wallenberg

except the Smoltsov note had been completely obliterated.

The Swedish government then pressed the Soviets to continue

their investigation.

One final comment on the Gromyko letter and its continuing

effect on the fate of Raoul Wallenberg is made in an article

in the March, 1981 issue of McClean's Magazine. The author

is Yuri Luryi, an expert on Soviet law

who now lives and teaches in Canada:

"The sad thing is that it was Gromyko who signed the

letter back in 1957. He was simply a deputy of the foreign

minister then, but now he is a member of the Soviet Mount

Olympus. He is one of the gods who never makes mistakes.

One panelist in Sweden (Wallenberg Hearings, January, 1981)

said that until Gromyko is out of power, they do not expect

any positive change in the Soviet approach to Wallenberg's

fate."

July 1981

It has taken the world over 50 years to truly recognize

the greatness of Raoul Wallenberg - A man who acted while

others watched. The survivors of the Holocaust say "NEVER

AGAIN". Let us take these words and apply them further:

Let us apply them to those who have stood silently as Raoul

Wallenberg disappeared into the horrors of the Gulag. Raoul

Wallenberg is not only a symbol of injustice, but also a

symbol of indifference. Let us act now.

In

Acknowledgement

We are indebted to the following authors and publications:

WITH

RAOUL WALLENBERG IN BUDAPEST. Per Anger (Holocaust

Library).

RIGHTEOUS

GENTILE; THE STORY OF RAOUL WALLENBERG, MISSING HERO OF

THE HOLOCAUST, John Bierman (Viking Press, New

York. Allen Lane, London).

WALLENBERG,

THE MAN IN THE IRON WEB. Elenore Lester (Prentice

Hall).

RAOUL

WALLENBERG; HERO OF BUDAPEST. Eugene Levai (Central

European Publishing Company)

WALLENBERG.

Kati Marton (Random House)

RAOUL

WALLENBERG; ANGEL OF RESCUE. Harvey Rosenfeld

(Prometheus Books)

ON

THE 35YEAR OLD TRAIL OF A MISSING HERO. Yuri

Luryhi (McClean's Magazine)

THE

WALLENBERG MYSTERY-FIFTY FIVE YEARS LATER.

William Korey (The American Jewish Committee)

RAOUL

WALLENBERG-REPORT OF THE SWEDISH /RUSSIAN WORKING GROUP.

(Ministry For Foreign Affairs)

Click

here for a bibliography.

The

photographs taken in Budapest are the work of Thomas Veres,

Raoul Wallenberg's personal photographer. In order to escape

detection, many of the photographs were taken by Veres with

a camera hidden in his scarf. A tiny hole in the scarf provided

access for the camera lens. These secret photographs provide

a searing indictment of Nazi brutality.

Tom

Veres lived and worked as a photographer in New York. When

he died in 2002, the world lost a one of a kind individual

and the Committee lost a great friend.

|